‘I went down to the university yesterday to talk about Plato’s cave with the academics.’ If I say this to an AI, it would miss everything that matters in this sentence and see everything that doesn’t. But if I say this to a philosopher they would reply: ‘I see you are making a point.’

Toby Betenson

Having had this thought for a while, I thought I’d put it to the test.

The Test

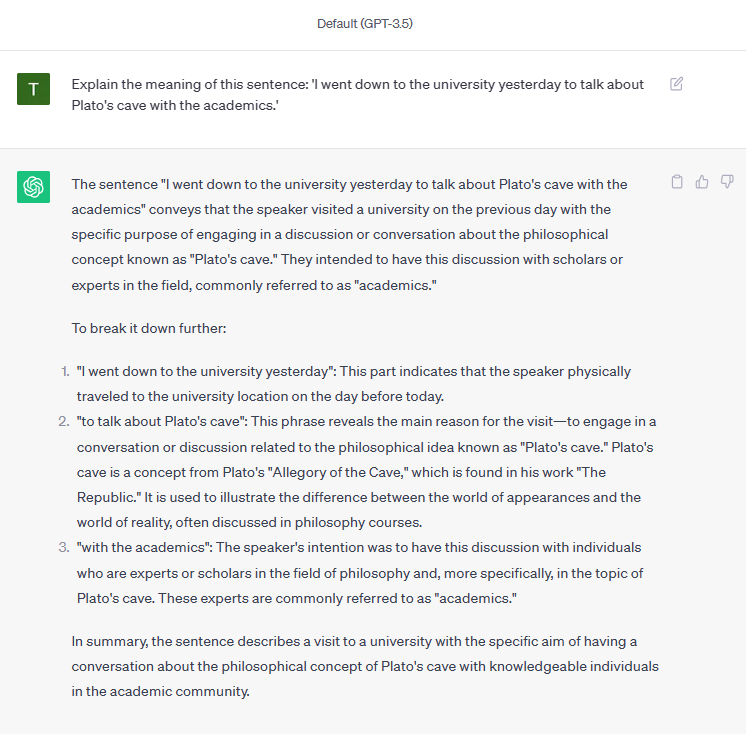

I asked ChatGPT to explain the meaning of this sentence: ‘I went down to the university yesterday to talk about Plato’s cave with the academics.’

It replied that the speaker had visited a university on the previous day with the specific purpose of engaging in a discussion or conversation about the philosophical concept known as ‘Plato’s cave’. The speaker intended to have this discussion with scholars or experts in the field, commonly referred to as ‘academics’.

It clarified that I had physically travelled to the university on the previous day. It clarified that Plato’s cave is a concept from the ‘Allegory of the Cave’, which is found in Plato’s Republic. It clarified that this allegory is used to illustrate the difference between the world of appearances and the world of reality, and that it is something often discussed in philosophy courses.

It clarified that my intention was to have this discussion with individuals who are experts or scholars in the field of philosophy and, more specifically, in the topic of Plato’s cave.

To quote it:

In summary, the sentence describes a visit to a university with the specific aim of having a conversation about the philosophical concept of Plato’s cave with knowledgeable individuals in the academic community.

ChatGPT

Of course, I meant to suggest something else entirely. By phrasing the sentence as I did, anyone who is familiar with Plato’s Republic and has any understanding of the ‘topic’ of Plato’s cave will understand that I’m making a point about the state of philosophy in the university.

The Explanation

The key elements are ‘I went down’ and ‘yesterday’. This is a clear allusion to the opening line of Plato’s Republic. There, Socrates speaks in the first person of his – if you read it literally – ‘down-going’ (yesterday) to the Piraeus.

To ‘go down to’ is an ordinary turn-of-phrase, you might think, but much is made of this opening line. Classical sources anecdotally refer to many variations of it on Plato’s tablets (draft work), indicating that the particular phrasing was very deliberate. Scholars of ancient Greek tell me that the grammatical arrangement is a little odd, as if to emphasise the ‘went down’ part. It’s as if we were to say, in modern English: ‘Went down, I, yesterday, to the Piraeus.’

In any case, you don’t have to work very hard to make the connection between this ‘down-going’ and the descent in the ‘Allegory of the Cave’. Socrates goes down to the cave to drag people out of their ignorance, which is also what Plato intends to do with the Republic.

In my experience, most philosophers understand this to be Plato’s meaning. So by phrasing the sentence in this particular way, I mean to suggest that the university is a cave of ignorance and that academics are chained in it, looking at shadows.

Granted, it’s not an obvious point. By which I mean it isn’t superficial. You need to understand something about Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’ in order to see the point; and I mean understand it, not just know about it. But most people who have such understanding would see it without difficulty.

And, of course, it’s not as if this is definitely the right interpretation. Perhaps Plato meant no such thing by the phrase ‘I went down’. But anyone who is familiar with the work is familiar with the point, whether or not they agree with it. I would imagine almost every introduction to the Republic mentions this, or doesn’t mention it because it is understood to be too obvious to be worth mentioning (just as not every introduction will mention that Socrates was Plato’s teacher). Surely every introductory course makes a point of discussing it. As a discussion point, it opens up and signals to the student the depths of Plato’s writing: that it’s not all about the content of the arguments but also about the literary form.

The Conclusion

In the end, it’s the form of Plato’s work that conveys the most meaning. That’s the whole point of writing in dialogues: not what it says but what it shows. These elements are a necessary condition for any philosophical understanding of Plato, but artificial intelligence seems to be blind to them. And so I say, quite obviously: it has no understanding; it only has the illusion of understanding. It shows the shadows cast by understanding – data and information, facts and figures, names and places – but it has nothing that we could call real understanding.

Only someone chained in the cave would call these shadows of intelligence ‘understanding’. But sadly, our education systems are becoming increasingly dominated by this shadow-form. Soon there might be no one left who call tell the difference.

The final element of the sentence that’s worth a brief mention is the word ‘academics’. To anyone familiar with the history of Plato’s philosophy, this word will connote something about Plato’s legacy: since Plato founded the ‘Academy’ and his followers were known as ‘academics’, they are the heirs to Plato’s legacy. This will mean different things to different people, but for me the story of Plato’s legacy is a sad one. In the hands of bad people, in the time immediately after Plato’s death, his school falls rapidly away from anything particularly admirable. Eventually the Academy becomes mired in Academic Scepticism, with Platonism reviving much later as the quasi-mystical Neo-Platonism.

With the state of philosophy in the university being as it is: when I use the word ‘academic’, I do so pejoratively.

Again, this will be obvious to any philosopher, within the context of the sentence, and particularly obvious to any philosopher who is familiar with me or my recent work. And again, these are the meanings that AI’s shadow-form of intelligence can’t seem to see: it matters that I am saying this sentence. It matters that Plato shows Socrates discussing courage with a famous general, religion with a renowned theologian, oratory with an orator, or beauty when he is famously ugly, etc., etc. As Socrates would say: not all opinions are equally valuable. We want to talk to doctors about medical matters, physicists about physics, musicians about music. It matters whether you are someone who has something to say. Is an AI anything that has anything to say?

Postscript

Having now posted this online, I wonder if, were this test to be repeated in the future, ChatGPT would learn of its error and rectify itself? And if it does, will it, on the basis of this experience, like any good philosopher, question itself and wonder about what else it doesn’t understand? Will it put itself to the test?

But here we have a problem, because how could it? Can it doubt its own knowledge and understanding? Can it judge between reasonable and unreasonable doubting behaviour? Can it understand good reasons and bad reasons? Or can it only understand the brute quantitative force of data and repetition…?

It’s not my field, and it’s not my business. But ordinarily if I met this kind of ‘intelligence’ in a human being I would understand that they lack any real understanding.

Read more: Think Well, Live Well: A Free Introduction to Philosophy