Aristotle was a very down-to-earth philosopher. He is always contrasted with Plato in that sense. Aristotle said we should trust observation over theory, and trust theory only if it matches up with the observable world. We should be wary of getting lost in the world of the intellect. Believe in what you can see, not in what you can imagine.

Most of Aristotle’s work was much closer to what we would nowadays describe as science, rather than philosophy, and this scientific approach is carried through all of his thought. If you want to understand something, look first, think after. That might be a good slogan for Aristotle’s approach.

So what do we see when we look at the world? Well, we see a lot of things. We see various objects, places, people, activities, qualities and quantities, properties and principles…it’s a bit of a mess and can get very complicated. How can we tidy up our observations of the world, such that we can make some sense of what we are looking at, abiding by our ‘look first, think after’ principle?

Think what you do when you are trying to tidy a messy desk or a room. A first step might be to organise what we find into various ‘types’ or ‘kinds’ or, to use the Aristotelian word, categories.

The Categories

The word ‘category’ comes from Aristotelian philosophy, via an Ancient Greek root word that means something like ‘to accuse’ or more colloquially ‘to point the finger at’. When Aristotle starts to tidy up our observations of the world, his first step is to group things together according to the principle of what we ‘point the finger at’ and say something like ‘that is a…’. So we point at a horse and say ‘that is a horse’. We point at a man and say ‘that is a man’. We point at a shoe and say ‘that is a shoe’. Etc.

On closer inspection, we see that we can also point at the qualities of these things: ‘That is a brown horse.’ ‘That is a tall man.’ ‘That is a brown shoe.’ Note, we now observe that there is something ‘pointed at’ that is common to both the shoe and the horse; namely, that they are brown. So we have discovered a new type of thing that we ‘point the finger at’: in this case, not an object, but a colour. And we can also point at blue and say ‘that is a colour’, and yellow, red, etc.

These things that we can ‘point at’ in a lot of different instances – such as the brownness in brown shoes, brown horses, brown curtains, etc. – are called ‘universals’. The idea of a ‘horse’ is also a universal, because there are lots of horses, in a horse race for example, and we can point at any of them and say ‘that is a horse, and that is a horse, and that one, and that one too’, etc.

These ‘universals’ can be contrasted to those things that we only ‘point at’ and say of one individual, such as when we point at the winning horse, or if I point at my brother Jack and say ‘that is my brother Jack’; these are called ‘particulars’.

The difference between universals and particulars shows us that some of these types of things we ‘point at’ or ‘say of’ seem to extend more broadly than others; sometimes very widely, such as ‘that is a physical object’, sometimes so narrowly that it is confined to one particular instance. It’s ‘said of’ a winning horse that it is that horse (we tend to use proper names to identify particulars), but also that it is a winning horse; and also that it is a horse, and a mammal, and a living thing, and a physical thing. But not all physical things are living things, not all living things are mammals, not all mammals are horses, not all horses are winning horses, and not all winning horses are that winning horse.

We end up with a hierarchy of kinds of things we ‘point at’ or ‘say of’ other things. At the bottom of the hierarchy are individual objects: these are the narrowest possible terms. At the top of the hierarchy, Aristotle places what he calls the ‘Categories’. These are the points at which you cannot go higher in the hierarchy of what is ‘said of’ or ‘pointed at’. They are the broadest possible terms. He identifies ten of these categories: Substance, quantity, quality, relatives, somewhere, sometime, being in a position, having, acting, and being acted upon.

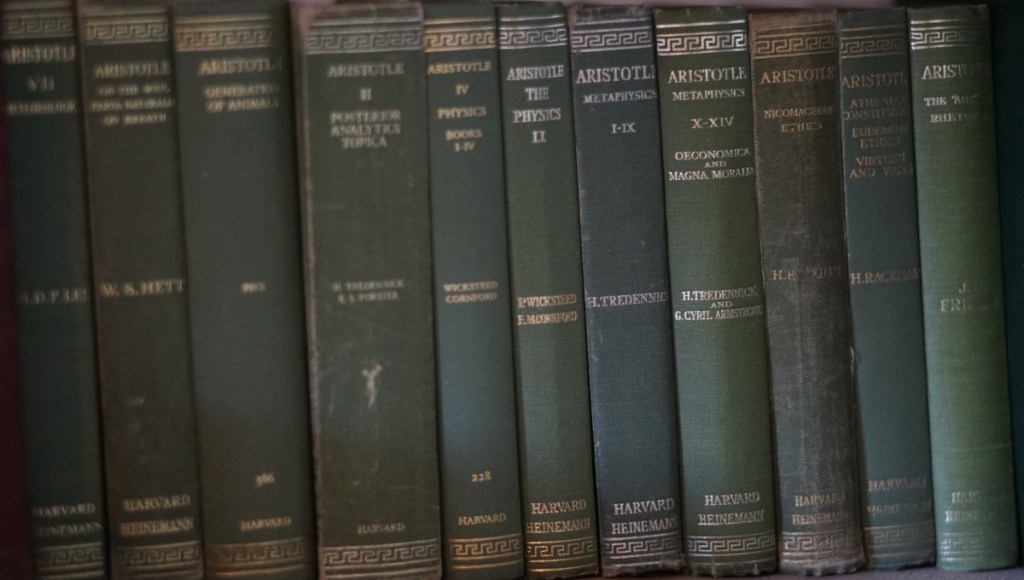

Swiftly we are getting into complicated territory, and Aristotelian metaphysics is very complicated territory. (If ever you needed an example of how philosophy understands ‘clarity’ to be a virtue of thought but not necessarily of style or expression, you should read Aristotle’s metaphysics and understand that it is an example of truly great philosophy.)

To cut a long story short, Aristotle observes what we ‘point at’ and ‘say of’ various objects and organises them into various groups, following the hierarchy of what is ‘said of’ to the top and eventually settling on these categories as being definitive of what it means to understand the world.

And that’s it. As complicated as it becomes, it remains very economical: we only talk about what we can observe in the world. What this means is that there is nothing more that we need to find in order to understand the world or anything in it; everything we need it right in front of us. Nothing is hidden. We don’t need to drift off into some other-worldly realm of Forms. We just need to apply the right categories.

Read more: Think Well, Live Well: A Free Introduction to Philosophy