The meaning of the word ‘happiness’ has never been straightforward. Most of us aren’t clear what it means in our own language, let alone what it meant in an ancient one. This makes translation difficult.

Most widely-available translations of ancient Stoic works think it easier to just say ‘happy’ and trust that people will understand more or less the right thing by that. But consider this popular passage from Epictetus, in translation:

Show me a Stoic, if you have one. Where? Or how should you? You can show, indeed, a thousand who repeat the Stoic reasonings. But do they repeat the Epicurean less well? Are they not just as perfect in the Peripatetic? Who then is a Stoic? As we call that a Phidian statue which is formed according to the art of Phidias, so show me some one person formed according to the principles which he professes. Show me one who is sick, and happy; in danger, and happy; dying, and happy; exiled, and happy; disgraced, and happy. Show him to me; for, by Heaven! I long to see a Stoic.

Epictetus, Discourses, Book II, Chapter XIX: ‘Concerning those who embrace philosophy only in words’

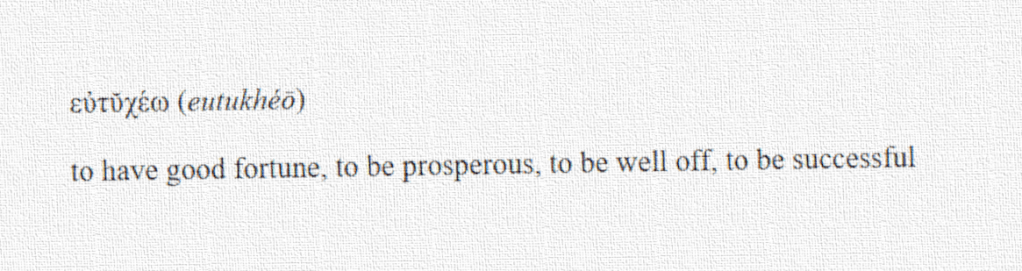

The word to focus on here is what is commonly represented in translation as ‘happy’. I think it is an important word, and I’m not sure ‘happy’ is good enough. Just as we understand a difficulty in translating Aristotle’s ‘Chief Good’ of eudaimonia as ‘happiness’ because it means more than just ‘feeling good’ or ‘being content’, so too I think this word – in the original a case of ‘eutukhéō’ – conveys more than a feeling. It is a feeling, but also a judgement.

This word, in other contexts, would mean something more like being ‘lucky’ or ‘fortunate’ or ‘successful’ or ‘prosperous’ or ‘having had things turn out well’. The root of the word is ‘good luck’. And so in this case, it seems to me that a phrase like ‘show me one who is sick and considers themselves lucky’ would capture the original meaning more accurately.

I might be wrong. I’m no expert on translating ancient languages, and I’m overwhelmingly in favour of respecting a translator’s informed opinion and taking their word for it on most matters. But I also know that sometimes words do not directly translate, and in those cases it’s useful to have some insight in order to understand this, or else you might be led astray.

I pay close attention to these words, when they matter, but go along with the rest. For me, it doesn’t much matter what ‘sick’ means, or ‘in danger’, or ‘dying’, or ‘exiled’, or ‘disgraced’. There might be some connotations in these original words that I’m missing, but they won’t make a significant difference to how I understand the Stoics.

The word ‘happy’ is different. If I understand ‘happy’ to mean ‘feeling good’, then that is one meaning, and I might ask how one can reasonably expect to ‘feel good’ whilst sick or dying. But it’s different if I understand ‘happy’ to mean ‘considers themselves lucky’ or ‘fortunate’. I can sit in illness (as I do, currently writing this, as it happens) and consider myself fortunate because I understand that it is a minor illness and it will soon pass (because I have a healthy immune system) and if not then things go as they will go. Illness is a natural part of life, but only a part. And my wife and daughter are upstairs and well.

It’s very intuitive to describe this state of affairs with the phrase: ‘sick, but considers himself lucky.’ But I don’t ‘feel good’ and would struggle to describe myself as ‘happy’ in that sense because I would rather feel better. I ‘consider myself lucky’ now, but I do not consider myself ‘happy’ now; there is a difference there. And if a Stoic would say that I can be happy now or I will never be happy, then that would seem to mark me as a failure of a philosopher.

Change the word, though, and it’s a different story. You can consider yourself lucky now, or fortunate, or well off, or you will never consider yourself lucky/fortunate/well off. That is true, and it can always be true, if you follow the Stoics’ reasonings. This can be true even in grief; for whilst you would struggle to describe yourself as ‘happy’ in grief, you can still consider yourself ‘fortunate’ for having known and loved the person you have lost.

For me it’s a very important change, but I leave it to your judgement. I think it’s morally impossible to consider myself ‘happy’ when my loved ones suffer, or ‘happy’ when I experience remorse, or ‘happy’ when I hear about terrible injustices in the world. If Epictetus asks me to be ‘happy’ with these things then I will reply that he asks me to do something that I cannot, and that puts a block on any acceptance of Stoicism (for me). But change the word to ‘fortunate’ and it starts to look different.

My loved ones suffer, and I am sad about this and certainly not ‘happy’, but I am fortunate to have people that I love so dearly that I suffer when they suffer. And of course I know that suffering is an inevitable part of life, so I accept my good fortune to have the privilege of suffering with them. Suffering is inevitable; me suffering with them is not. But would I rather not be there? Would I rather not care?

I am not happy to learn that I have done something morally wrong, but I am fortunate to have at least recognised the error of my ways and have some opportunity to make amends; better that, and suffer in remorse, than continue in blissful ignorance. I know it is better to suffer wrong than to do it.

I am not happy to hear about terrible suffering and injustice in the world, but I am fortunate to be someone whose soul is healthy enough to recognise and be affected by these things. Would I rather dismiss them as if they are nothing to me?

Once again I have found a way to explain to myself why a philosopher would choose to suffer, even though they have equipped themselves with the ability to avoid all suffering. It makes sense to suffer, sometimes. It might not feel good but it is right. And for a philosopher that is more important. But I accept that this idiosyncratic explanation puts me at odds with some Stoics, and especially with later expressions of Stoic principles (such as Spinoza), and for that reason I probably would not consider myself to be one of them.

Read more: Think Well, Live Well: A Free Introduction to Philosophy