It might sound odd to say that Plato’s discussion of political philosophy shows us important truths about how to live well. For many of us, thinking about politics is likely to make us feel more anxious and depressed, not less. But it makes more sense when you consider why Plato is discussing political philosophy in the first place.

Plato is looking for an answer to age-old Socratic question ‘what is it to live well as a human being?’. Perhaps we suspect, with Socrates, that this involves the virtues like justice, courage, or temperance, but what are these virtues?

Plato recognises that answering these questions directly is difficult because the answers are difficult to see. How can we make it easier to see?

Scale It Up

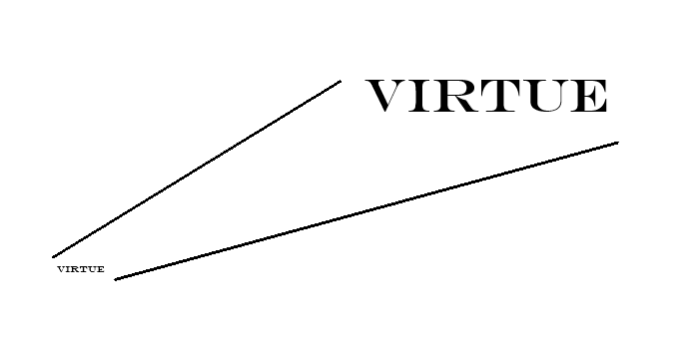

One way that we can make something easier to see is to make it larger.

Imagine you are short-sighted and struggling to read some small text. If only the letters were larger, then it would be easier to read! If you had a larger version of the small text you are trying to read, you could read that larger version first, see it clearly, then you’d only have to compare it with the smaller version and see if it’s similar. That would be a lot easier than reading the small text outright.

How can we do something similar for our ideas about virtue? How can we get a bigger image of ‘justice’ or ‘courage’ or ‘living well as a human being’, in order that we can see them more clearly? How can we see these things on a larger scale?

What if, rather than looking at what it is for a human being to live well, we looked at what it is for many human beings to live well?

Wouldn’t that give us a bigger, scaled-up image of what we’re looking for? ‘Many’ is bigger than ‘one’, after all, and bigger things are, as a rule, easier to see. We already have these images in groups like families, communities, villages, tribes, cities, and nation states. These ‘larger images’ are much easier to see than the ‘smaller image’ of an individual human life.

And wouldn’t we say that these larger images, these groups of people, can be described as virtuous in exactly the same way as the smaller image of the individual person? Can’t nation states be described as virtuous or vicious, courageous or cowardly, conservative or liberal, just or unjust?

Plato thinks we can do just this: by looking at the ‘larger image’ of the nation state, we can more clearly see what it is to live well as human beings. Once we have that larger image, we can then scale it down to the smaller image of the individual human being and apply what we have learnt.

The Parts of the Ideal State

When Plato looks at this larger image, in his political philosophy, he sees a well-functioning state as one that is composed of various parts: the parts that rule, the parts that protect, and the parts that provide. In simple terms, these are the rulers, the warriors, and the workers.

The rulers decide what should be done and give instructions. The warriors obey and enforce these instructions, and protect the rulers and workers. The workers provide food and any other material goods, under the protection and enforcement of the warriors. A well-functioning society is one in which each part fulfils their role in harmony with the whole.

In order for this to be harmonious, each part much be content to play their part. This means people should do what they are naturally best suited to do and society should encourage them in this direction.

If you are naturally angry and violent, you are ill-suited to make ceramic pots or tend to animals, but you would make a good warrior. If you are naturally timid and conscientious, you would make a lousy warrior, but you might make a very good artisan.

There are attributes that are more or less suitable for each part in society. Warriors should be brave, strong, loyal, and patriotic, but they should not be motivated by money or else they will be vulnerable to bribes; farmers should be patient, hard-working, conscientious, but they need not concern themselves with anything beyond their patch of land; traders should be motivated by money, but they must be fair-minded or else timid enough to fear enforcement; artisans should be skilled and creative, but they need not be particularly strong or brave. The virtues of each are determined by the role they play in society.

Who would make a good ruler? For Plato, it can only be the philosopher.

The role of the ruler is to decide what to do and give instructions. It’s important that they know what they’re doing. Only a philosopher understands the world as it really ‘is’ as opposed to how it ‘seems’, and so only they have accurate knowledge: everyone else is living in the shadow world of images and representation. We should put those who know best in charge and this means that only philosophers – the ‘lovers of wisdom’ – should rule.

Until philosophers are kings, or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy, and political greatness and wisdom meet in one, and those commoner natures who pursue either to the exclusion of the other are compelled to stand aside, cities will never have rest from their evils – nor the human race, as I believe.

Plato’s Republic

Failed States

Most of Plato’s political philosophy is about showing the disastrous consequences of allowing anyone other than a philosopher to be in charge. I’ll paraphrase and sketch for the sake of brevity, but even in its sketchiest paraphrasing Plato’s point is compelling and prescient.

If you put a trader and money-maker in charge, they will use their position to amass personal wealth, the society will become dominated by the desire for material wealth, and everything will suffer: farmers cash in on the most productive output, neglecting the long-term health of their land and livestock, leading to famine; artisans don’t make the best but only the best-selling, leading to a gradual decline in prices (and quality), and they suffer more and more in their work as it becomes a soulless grind; warriors sell their services to the highest bidder, even if this means protecting the unjust. The rich get richer and use their riches to oppress the poor, who only get poorer. Eventually, the poor rebel violently, if they can.

If you put a warrior in charge, they will use their position to enhance only their glorious reputation, society will be dominated by a lust for glory, and everything will suffer: warriors will be more concerned with outcompeting each other, rather than the enemy; traders and money-makers will waste money on outlandish displays of status, and will be free to trade injustice for the material means of displaying status; the society will find itself dragged into needless and damaging wars, because a warrior always needs an enemy to fight against in order to prove their strength and gain glory. The warrior cannot stand someone else being above them, so gradually takes more and more power for themselves, gradually exerts more and more power over others. They become a tyrant. Eventually, the powerless rebel violently, if they can.

And what about democracy? For Plato, democracy is the worst form of government, worse than all the others, because it is so vulnerable to corruption. As a form of government, it lacks direction and cares little for the truth. If you put the people in charge then those people will, knowing no better, vote for pleasant-seeming cave-shadows over truths that they do not understand. Those who want power know this, and can easily manipulate those cave-shadows to their purposes. Traders and money-makers use the will of the people to make more money; warriors and glory-seekers use the will of the people to justify war; etc., etc.

According to Plato, democracy is nothing other than a rule by the mob, and the mob is perpetually vulnerable to being led astray by a charismatic but self-interested person who wants power at any cost. This will inevitably lead to chaos and tyranny.

Plato’s views on democracy are dated. Most modern democracies have found ways to counteract the tendency to descend into chaos and tyranny. Even so, his criticisms continue to ring true, and they always ring truer when democracy creaks under the influence of charismatic but self-serving leadership contenders. You might be forgiven for thinking that this seems to be happening more and more. To my mind, it’s in these times that it’s important to remember the real virtue of democracy: The point of democracy is not to find the right answer, but to allow every individual to participate in their own government.

We choose democracy not because it’s the best, but because its better than any alternative in which people are not permitted to govern themselves. People make mistakes in governing themselves all the time; why should we expect groups of people to be any different?

Individual Virtue

Remember that Plato’s discussions of political philosophy had a purpose, and that purpose was to offer up a larger image of ‘virtue’ or ‘living well’ in the nation state in order to make it easier to see what ‘virtue’ or ‘living well’ was in an individual human life. We’ve seen that, in the state, ‘living well’ means each part playing its part, with those who ‘know best’ being put in charge.

It’s a clear allegory. If you look to yourself, as an individual, you will see various parts. These parts want different things, pulling you in different directions. Your body wants pleasure and freedom from pain: you want to be comfortable, warm, safe, and well fed. Sometimes you need to provide for your needs and wants, like the artisans and farmers in Plato’s allegory.

Your spirit might want something else: it wants to compete and win, and it is glad to face some discomfort in pursuit of this goal. Sometimes you need to fight for what’s rightfully yours, like the warriors in Plato’s allegory.

And like the ideal state, the individual functions best when each part is allowed to play its part without coming to dominate the whole. You want these competing parts of yourself to be held in balance and governed by a ruling faculty.

Your inner philosopher – your ‘reasoning faculty’ – will enable you to weigh up your competing desires and decide on the best course of action. It’s likely that you will have to strike a balance and give each competing desire its proper place. Allow your bodily appetites to be satisfied to the extent that it doesn’t damage you or prevent you from achieving your spiritual goals. Allow your spiritual goals to direct your life, but don’t let them dominate to such an extent that they make you ill. A nation of warriors will be constantly at war with itself and others; it will quickly die. A nation of farmers and artisans will be comfortable and well fed, until the invading army arrives…

You need these various parts of yourself just like a nation states needs its various parts. But this always requires some governance. Someone needs to keep the warriors in check and tell them what to do; someone needs to stop the merchants taking over.

This is a difficult task and it requires some know-how. It’s only your reason, your governing faculty, that knows what it’s doing because it’s only your reason that can think things through. If you let that reason be your guide, put it in charge, and let it manage the competing parts of yourself, you will never go far wrong.

Read more: Think Well, Live Well: A Free Introduction to Philosophy