According to Aristotle’s view, wisdom lies in the ability to identify and choose the happy middle, for you, relative to yourself and your purposes. One part of this is philosophical: you need to look, think, and understand what the happy middle is, for you, for any given virtue. The other part is practical: you need to choose what you identify as the happy middle. This choice is an action; it is something that it done, not only something that is thought about. The ability to make that choice depends on more than just thinking about it: you need to train yourself to make the right choices. You need to make them habitual.

This suggests there are two things that are necessary for moral understanding, according to Aristotle: education and habituation. You need to learn what the happy middle is and then you need to practise it. You can teach yourself, through suitably informed philosophical reflection, but it’s often easier to just have someone show you the ropes. Putting it into practice is something we all have to do for ourselves.

Your aim is to become the kind of person who habitually makes the right choices and finds the happy middle. To begin with, this process requires deliberate thought, but with practice and habituation it becomes a kind of instinct, a second-nature that you can follow without thinking. When faced with a situation in which you could be cowardly or courageous or reckless, you choose to be courageous; when faced with a situation in which you could be a bore or a wit or a fool, you choose to be a wit; when faced with a situation in which you could be shy or confident or arrogant, you choose to be confident.

Over time, with practice, you mould your character into someone who has a habit of making the right choices and finding themselves in their happy middle. In this way you will give yourself the best chance of achieving your purposes and living a good life. This, for Aristotle, is what it is to be an excellent human being.

And so he sums it up:

Virtue […] is a state of character concerned with choice, lying in a mean, i.e. the mean relative to us, this being determined by a rational principle, and by that principle by which the man of practical wisdom would determine it.

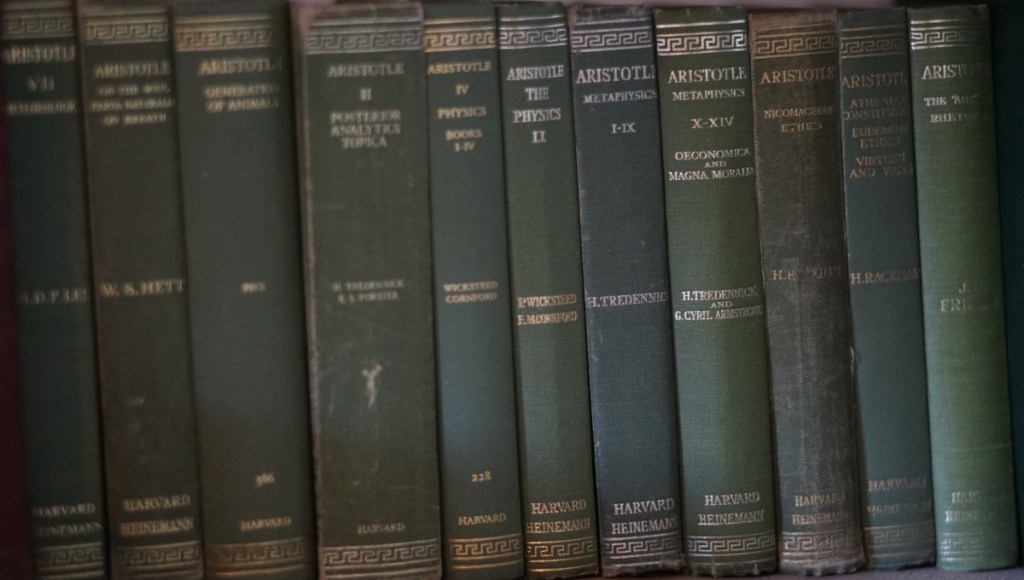

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

The Ideal Human Being

The last clause in that sentence is a perpetually frustrating one: ‘…that principle by which the man of practical wisdom would determine it.’ I’d encourage you not to read too much into it; I think it says less than it seems.

Firstly, it’s of no relevance at all that this is a gendered ‘man’ – it just means ‘human being’ (though Aristotle was among the least admirable of ancient philosophers when it comes to gender equality).

Secondly, this human being clearly doesn’t actually exist: it’s an appeal to an ideal, not an actual person.

Thirdly, it is not an appeal to follow the instructions of this ideal person, as if there were this ideal philosopher-dictator drawing up a list of rules in the sky that would tell us what to do. Aristotle is not giving us instructions; he is giving us an analysis. A practical analysis, granted, that gives us some practical advice, but it remains an analysis.

What Aristotle is appealing to is an idea of the way that human beings think and act when we are operating at our most excellent, when we are being most fully ourselves at our best. As he says, human beings are rational animals; it is our rationality that defines us as human beings; so we operate at our best when we are being rational. And so this ‘rational principle by which the man of practical wisdom would determine it’ means little more than what an ideal human being would think when they are thinking well.

In short, it is the philosophy of the ideal human being, whatever we understand that to be.

Aristotle’s philosophy, which begins with his down-to-earth metaphysics and theory of causation, which shows us what a human being is and in turn what we all want (happiness) and how to get it (be excellent and find the happy middle), is his best attempt at offering that philosophy of the ideal human being.

In a sense that is what all philosophers are trying to do. But as far as Aristotle’s followers are concerned, he offers the best of any attempt that has been made: he offers us a comprehensive worldview, a depth of theory that conforms to what we can observe in the world elegantly combined with an economy of theory that requires nothing beyond what we can observe. There are no other-worldly skyhooks like Plato’s Forms, nor anything that goes against our day-to-day beliefs like Socrates’ paradoxical claim that it is better to suffer evil than to do it.

Aristotle tells it as it is. According to Aristotelians, any properly-functioning human being will agree with these ‘rational principles’ because they are the most rational of principles, the ones that conform most to our observations of the world and human behaviour. They think they have the right answer, the answer that an ideal human being would agree to when they are thinking at their best.

And so if I am permitted to offer a tentative rehabilitation of Aristotle’s famous line:

Virtue is a state of character concerned with choosing the happy middle, relative to us, this being determined by a rational principle, which is what an ideal human being would decide when they are thinking at their best.

Read more: Think Well, Live Well: A Free Introduction to Philosophy