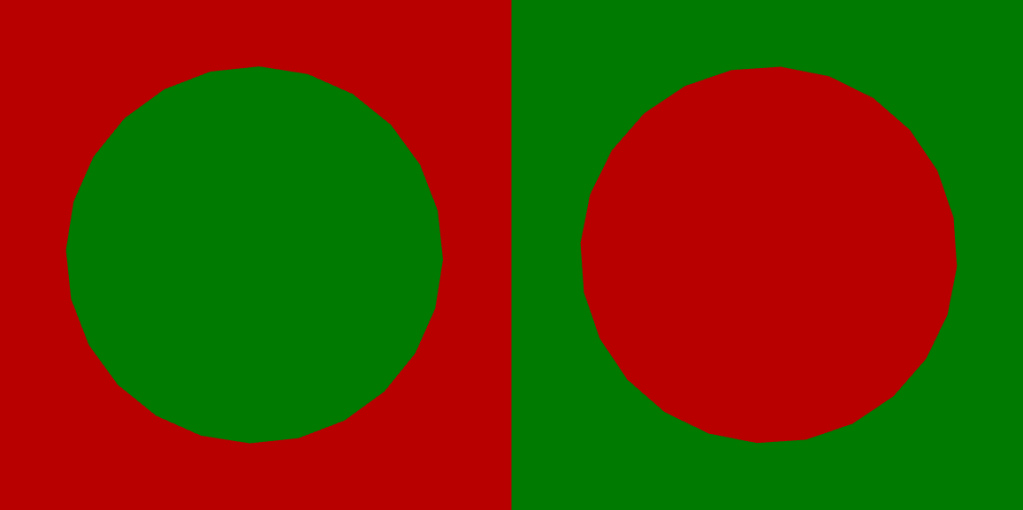

Do you see a difference between the circles above? Perhaps you do. Is it obvious? Perhaps it is.

And if something important depended on whether or not a circle was judged to be red or green, would you be confident in your judgement? Perhaps you would.

But some people would not see any difference between the two circles. If you have a particular form of colour blindness, the colours red and green will look the same (or very similar) as one another. As a result, you will not see a difference between these two circles, or if you do then it will not be obvious. You might have to work hard to discern the difference.

Perception

Something I’ve observed in people’s reactions and judgements about mental health is like a kind of colour blindness. It shows itself as an inability to discern a difference between two things that are obviously different.

They cannot discern the difference between someone who is lazy and someone who is dangerously depressed, or the difference between someone who is nervous and someone who is struggling with anxiety.

And because they can’t discern the difference, they treat one as if it were no different from the other. They tell the dangerously depressed person to pull themselves together, put some effort in, pick themselves up and get on with it. We’ve all had hard times, after all, times when we lacked motivation and struggled to see the point in things, but no one ever got better by sitting around doing nothing.

They tell the person struggling with anxiety that it’s simple: you need to toughen up. Everyone gets nervous.

These might be appropriate responses to laziness or nerves, but they are ludicrously inadequate responses to depression or anxiety and are just as likely to make things worse rather than better.

Of course it can just as easily go in the other direction. It seems to be more and more common for people to label sadness and nerves with terms like depression and anxiety and treat them as such with pills and therapy, even though these emotions are an essential and unavoidable aspect of the human experience. There’s nothing wrong with being sad or nervous, so it’s a mistake to pathologize them. This over-medicalising response can be just as damaging as a dismissive response, especially to a young person denied the opportunity to be sad, or angry, or to face and so work through their fears. In either case, it will not help the situation.

If their intention was to help, then these people have made a lousy judgement by responding in these ways. But it’s not their judgement that’s at fault, or their intention: it’s their perception.

As Epictetus said, people can only judge things as they seem to them. The problem is that these people cannot see the difference.

Correction

What can correct this? It’s not a matter of further evidence or data. No matter how many red and green circles you show a colour-blind person, they will never see the difference.

What is needed is a philosophical intervention. It begins with doubt: a prompt to ask a question, rather than assert a judgement. ‘What do I know?’

This question asks for a fundamental scepticism; a self-doubt and self-reflection. The person who cannot discern a difference between laziness and depression, or nerves and anxiety, needs to learn that they don’t know as much as they think, that there’s more to it than they realise. There are things that are real but that they cannot see because they are not in a position to see.

Most people aren’t willing to learn this. No one likes to learn they are ignorant (unless they are a philosopher). Because of this, they will get defensive and argue their case.

Imagine arguing with them. No amount of persuasion or rhetoric can make them see what they cannot see. ‘There is no difference in colour between those two circles!’ But how absurd does this look to the person who is not blind in this way?

I think most people who have near-experience of the reality of mental health issues can easily discern the difference; whether in your own experience, or in that of close friends or family, or in a professional capacity. It is obvious to them, like black and white. They show this in the judgements characteristic of these suitably-informed people: respect, compassion, understanding. They do not respond in the same way as the ignorant.

This is a lesson at least as old as Socrates: everyone has opinions, but some opinions count more than others.

Opinions count more when they come from a place of knowledge and understanding. There are lots of different ways to gain knowledge and understanding, and none of them start with knowing all the answers. Most of them start with a question.

If you want to know what it is to fly a plane, you should ask a pilot, or better, become one yourself; if you want to know what it is to fight in a war, ask a soldier; if you want to know what it is to be depressed, ask someone who knows what they’re talking about: a mental health professional, or someone with direct first- or second-hand experience.

These experiences make them what they are, and what they are is someone who has cultivated a certain understanding or gained a particular insight. If you still want to correct them, or weigh your opinion against theirs, be sure you know what they know. But ask yourself: are you sure?

I’m not sure about most things. But one thing I’m pretty clear about is that if you want to know the difference between red and green, don’t ask someone who sees no difference.

Read more: Think Well, Live Well: A Free Introduction to Philosophy