It is difficult to correct a misperception when it has become established: people tend to see what they believe, and so if they believe wrongly, they will see wrongly.

There’s no point appealing to ‘data’ in such circumstances because, as Epictetus would say, people can only judge things as they seem to them. And besides, there’s so much junk data out there that we’ve lost confidence in it.

Instead, I want to show you some images that I think speak for themselves. These are not projections of ideals; they are reflections of reality.

They show two different landscapes. One of these landscapes reflects the reality of growing vegetables in contemporary Europe. The other reflects the reality of livestock farming in contemporary Europe.

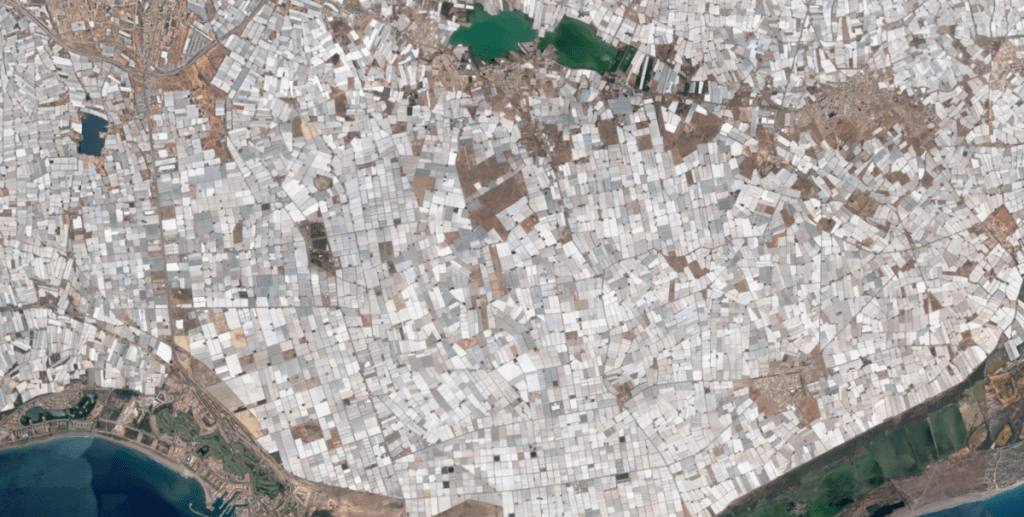

Thanks to Google for these images. This is Spain from space. What I want to draw your attention to is that little area of white on the southern coast.

What you’re looking at is plastic. Thousands upon thousands of acres of plastic. 40,000 hectares in fact. That’s bigger than Bhutan, or Belgium, or Hawaii, or about the same size as Switzerland, or about half the size of Lake Superior.

The Plastic Landscape

This is what it looks like to grow vegetables for Northern Europe in the winter: giant plastic greenhouses in Southern Europe (and elsewhere).

To state the obvious: nothing comes from nothing, and this plastic is no different. To further state the obvious: plastic is in essence a fossil fuel product. What results isn’t biodegradable, but neither does it last forever. When it loses its usefulness and efficiency, the greenhouse plastic is thrown away. People who know more about this than me estimate that about 33,500 tonnes of greenhouse plastic is discarded each year in this small part of southern Spain, with most of it becoming part of the landscape or making its way into the sea.

If you want to calculate the environmental impact of the veg on your plate, remember to include the plastic, the production of plastic, and the plastic that’s left behind. Because without that plastic, you would not have that veg: fresh, in December, in the UK.

The Livestock Landscape

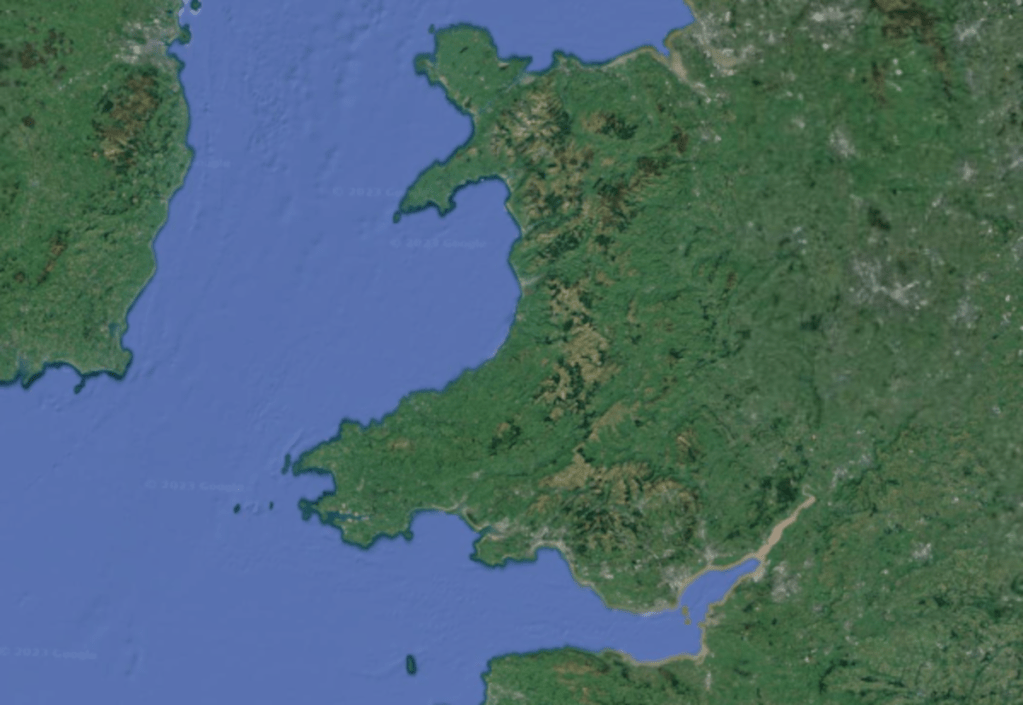

Now let’s look at somewhere different, somewhere that isn’t particularly favoured by global capitalist markets for growing vegetables: North Wales.

There isn’t as much sunshine in North Wales as there is in Spain, but there is a lot of rain. This is bad for veg, but good for grass. So in North Wales, we grow grass.

We can’t eat grass, but sheep can. They bloody love it; can’t get enough of the stuff. And they quite like sitting on a Welsh hillside too. They’ve been doing this for so long that the landscape has become adapted to their wants and needs. What does their landscape look like?

It’s undeniably green and pleasant. Note the many small fields, and with that the hedges and edges and scattered trees. These are natural habitats; this is where wildlife thrives. Here the circle of life continues without the need for any fossil fuel input. Things live and shit and die above the soil, becoming the soil, feeding what grows in the soil. Not a bit of plastic to be seen.

Give and Take

In the plastic landscape, we take everything and give nothing back. In the livestock landscape, everything gives back as it goes along.

Nothing comes from nothing, and nothing comes for free. There is a cost to everything that we do and especially to everything that we consume. This is true for livestock too: cows have their costs, as do cucumbers. But livestock take their place in a landscape that is sustainable: a landscape that gets what it needs from what it provides.

The same could not be said of the greenhouses of Almeria, which can only function by ravaging the soil, replacing what is taken with artificial fertiliser and controlling it with pesticides, so intensely over-using this one small area that it poisons the groundwater and will pollute the landscape for generations to come.

The New Colonialism

And that’s not to mention working conditions. British farmers regularly work for less than minimum wage, but they are often glad to do it: for them it is a privilege and a way of life. The same could not be said for those working in the greenhouses of Almeria.

Given the realities of what it takes to grow a varied and affordable plant-based diet all-year-round for Northern Europe, and were I rhetorically inclined, I would say that, in Northern Europe, a plant-based diet is the new colonialism: it is only made possible here, in this green and pleasant land, by trashing somewhere else.

Ironically, this is understood to be a good thing, from a certain ethical perspective. An argument often offered in defence of the kind of farming practices exemplified in the greenhouses of Almeria is that they are very efficient: by using this small piece of land in this way, you free up far larger pieces of land to use for other, greener, purposes. Like leisure and tourism.

That kind of weighing-up and paying-off has always been possible: in slavery, say. We ordinarily reject those arguments. We understand that we should solve our own problems, do our own work, and not pass it off onto an exploited minority in the name of ‘efficiency’: a cost-benefit analysis in which the cost is always theirs and the benefit always ours.

Think Locally

I speak from the UK, in the context of the UK: it will be different in other parts of the world. This is one of the lessons of the climate crisis that everyone should learn as soon as possible: what is right and best to do will depend on your particular context; and since contexts differ, there will be different answers about what is right and best to do, for you. And it follows from this that there will not be one universal ‘right’ answer, but a range of different ‘better’ answers.

Nonetheless, as it stands, given our dependence on fresh veg imports (UK production accounts for only 55% of UK veg consumption), especially in the winter, an undiscerning plant-based diet in the UK is only made possible by unsustainable farming practices.

In this context the answer is obvious, if you care to ask the question: buy seasonal and local, learn to love winter veg and potatoes, and be prepared to eat a lot of grains (but not rice…which will be imported and comes at a heavy environmental cost).

By contrast, UK production accounts for 65% of meat consumption, and of the 35% imported the vast majority of beef and lamb comes from grass-rich Ireland and New Zealand, which will have similar landscape stories to the UK. (It is a different matter for pork and poultry, for which the market forces of the modern world have favoured intensive systems.)

Many of the statistics about the environmental costs of livestock are based on a ‘global mean’. This is totally meaningless in the context of the UK. We have no rainforests to deforest; the vast majority of the feed for our cows and sheep comes from grass (not crops); and the food miles for the 100% grass-fed beef on my plate only just breaks into double-figures: the farm is 5 miles from the abattoir, which is 5 miles from the butcher, which is 2 miles from me. Walking around the landscape here, seeing how the farm operates and given what I understand about soil sequestration, I have absolutely no doubt that this beef is carbon and environmentally positive.

Livestock have been grazing here for 1,000 years (needless to say, without the need for artificial fertilisers) and their landscape has barely changed in that time (apart from the ever-encroaching housing estates being built around them). When managed well, the livestock landscape is a sustainable and regenerative system: it gives what it takes.

In terms of the environmental cost, the portion of beef fares far better than the portion of rice next to it; or the red pepper, from Spain, the production of which necessitated an unsustainable plastic landscape.

Related articles: The Environmental Impact of Beef Consumption: The Meaninglessness of the ‘Global Mean’, Romanticism and Livestock Farming