You need to think well in order to live well, and coming to understand what it is to think and live well is the proper business of philosophy. The process of philosophy, with all its theories and methods and technical discourse, is necessary to gain this understanding, but it is not the final end of this activity. Which means we should at some point leave it behind.

Is that true?

You need philosophy because you are ignorant: you don’t know what you’re doing, you don’t know what to do, you don’t know how to live, or why. You do not have true beliefs about what really matters. But if you do have true beliefs about what really matters, if you already know what you should do and how you should live, perhaps because you have investigated the matter through a long philosophical education, then why would you continue to argue about it?

What is there to argue about? You have your answer, a way of living that is consistent with itself and stands up to rational scrutiny; why continue to come up with more and more ways in which the alternatives fail?

Is it to convince other people of the virtues of your philosophy? But your lived example will be more convincing than any argument.

It is to further convince yourself, and reinforce your commitment to your art of living? But how can it help your art of living to do what is contrary to it, by getting lost in nit-picking arguments and trivialities?

The Stoics would say that we, in academic philosophy, have got things back to front. The whole point of philosophy is to think well in order to live well. To do this, we investigate the ideas that we have about things. And to do this we construct and appraise arguments for or against particular ideas.

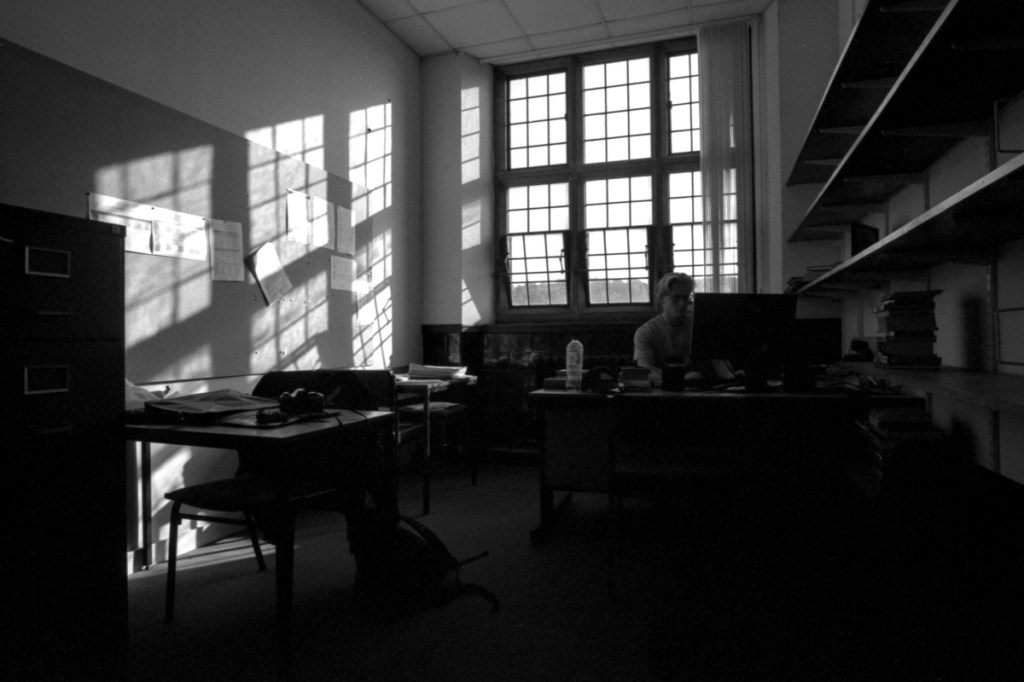

Academic philosophers end up prioritising the construction of these arguments at the expense of the reason for their construction. We get lost in our arguments, detached from our proper business as human beings, and end up painfully incapable of justifying the value of what we do to those who do not understand what we do. But this is our fault. We are not what we would claim to be. We live inconsistently with ourselves. We would claim to be philosophers, but we are not philosophers: we are critics and constructors of arguments, we are writers and speech-makers, we are sophists selling our wares.

We talk like philosophers but we do not live like it. It is all a show, and our behaviour shows it as such, as we strut about in the lecture theatre. We have sold ourselves at too low a rate, chasing material success in the marketplace of ideas. In this we are not lovers of wisdom but adulterers; we are married to our profession. We should stop this nonsense and return to our proper business as human beings, and that means leaving academic philosophy behind.

If your arguments are making you someone that you would not choose to be, then stop making arguments.

The Stoics would say as much, as would the Cynics, but I fear this is a contradictory idea. Of course we should not get lost in arguments and forget ourselves. But we should never stop investigating ourselves and our beliefs; we should never stop putting our thoughts to the test.

Because which of us has all the answers? Which of us is not plagued by errors? Which of us is not troubled by life? It’s clear that academic philosophy has many failings and that it has fallen a long way from its ideal. But that is not to say that it is all bad. There are many bad musicians and lots of bad music out there, but that doesn’t mean that music itself is bad and should be thrown away.

What is required is for those who are capable to preserve the discipline in its best and truest form. That is what it means for a philosopher to play their part. That is what Epictetus achieved. We should all hope to emulate that example.

Read more: Think Well, Live Well: A Free Introduction to Philosophy