Justice is a part of our idea of goodness, unequivocally. And so a sense of justice is good and very important: anyone lacking a sense of justice is no one we can admire and not someone we would choose to be.

But having a sense of justice makes you sensitive to injustice. With this sensitivity, any injustice is liable to make such a person miserable. And there doesn’t seem to be anything good about being miserable.

That seems to me to be a paradox of goodness, whereby something unequivocally bad comes from something unequivocally good. Justice is good, and happiness is good, but having a sense of justice makes us less happy. Having one good seems to deprive us of another. And I wonder what the solution to this puzzle might be.

Part One: A Monkey in a Cage Getting Cucumber

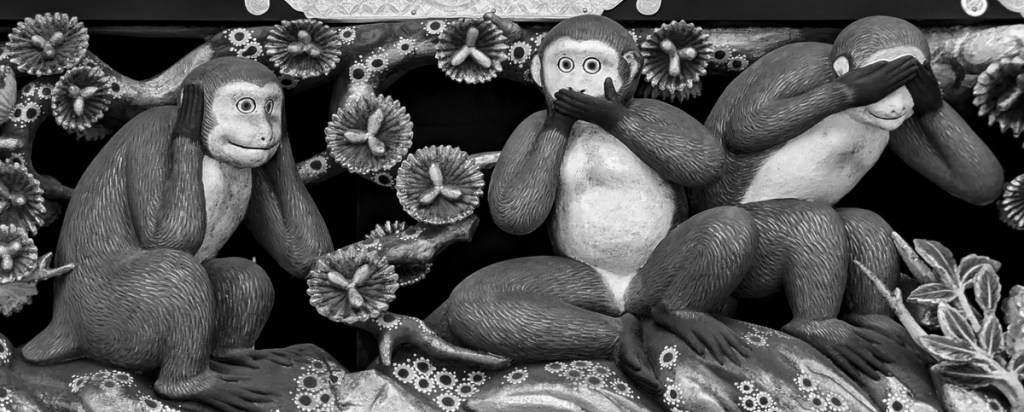

When introducing philosophy students to innate concepts of justice, a common approach is to talk about monkeys and cucumbers.

Two monkeys are in adjacent cages. One monkey performs a task, handing the scientist a stone, and is paid with cucumber, which is a low-value reward. She is happy enough with this and gladly eats the cucumber. Then the neighbouring monkey performs the same task but is rewarded with a grape, which is a high-value reward. The first monkey sees this. It provokes something in her. When she is asked to perform the task again, which she does, and is paid again in cucumber, she throws it back in the scientist’s face.

Why does the monkey do this? She was happy with the cucumber before. Why not let herself be happy?

It’s not the cucumber that’s the problem, or the task or the trade or the fact that she’s in a cage. If the monkey is alone, there is no problem: she happily makes the trade. If both monkeys are paid in cucumber, there is no problem: they are content to make the trade if they are rewarded like for like. But any perceived inequality generates a sense of unfairness (albeit only in the poorly-rewarded monkey). Suddenly the task seems like an imposition, the trade seems unreasonable, and the cage feels constrictive.

There are levels of this that can be tolerated but in the end we hit a limit and demand change. And while we are waiting for change, we rattle the cage, we refuse any reward, we refuse to do the task. We demand what is rightfully ours.

We get ourselves into a miserable state. Because it is a miserable thing to be a monkey in a cage getting cucumber. But only, apparently, when another monkey gets a grape. If we are all in cages getting cucumber, we are happy enough to carry on.

Isn’t that absurd?

So far this is only, as a metaethicist would say, ‘descriptive’ and not ‘normative’: that we feel this way about fairness doesn’t mean that we are right to feel this way. And so I ask why it is that, when I sense an injustice, I let it ruin my day?

I do my monkey’s task and perceive myself to be poorly rewarded. I shrug and move on: as I say, there are levels of this that can be tolerated. Most of my tasks are chosen for their intrinsic value anyway.

But the world is always trying to wring its bit of profit from you, and because of that there is a paradox that any decent person must face: the more you give and give freely, asking little in return, the less you will be valued. The phrase is ‘taken for granted’ and it escalates naturally. Do someone a favour once and they will say thank you; do it twice and they will say thank you; do it three times and four times and five times but not the sixth and they will reprimand you for your selfishness.

Conversely, those who insist on taking more than they give are always being rewarded with more than they are worth. They call it ‘profit’ and they are proud to keep it for themselves. How we praise the tiniest bit that they so charitably give back!

I recognise the absurdity of this (probably because I think about it too much): that the good get ever less than they are worth while the worthless get more (so much more). It’s at that point that I become the recalcitrant monkey and throw the low-value reward back in society’s face.

My resistance is perceived as a complaint about poor pay, in absolute terms. And when I say ‘pay’ I don’t mean only money but what is more valuable: esteem, respect, freedom, etc. But my complaint – to the extent that it is one – is only relative: it’s the unfairness of the situation that causes me trouble, even though my situation itself is absolutely fine. I would be happy to perform these tasks for cucumbers, only I can’t be happy to do so, and be asked to do more, while others do less for grapes.

I suspect it’s unavoidable: something essential to the condition of a thinking monkey. We need justice but we know this need will never be met, and because of this the thinking monkey will never be free from trouble. Shake your fist at the sky and demand recompense for all your suffered injustices, but what on earth could make-good the unimaginable and unforgivable atrocities of the past, or the present or future?

What is the outcome of this sensitivity to injustice? Only my grumpiness. No one benefits; I suffer, while others must suffer my grumpiness. I make trouble for myself. I am content with my situation and would be content with it. But I act as if I am oppressed, unappreciated, undervalued, etc. And I am. But what of it? It doesn’t change the absolute goodness of my situation.

Even so, self-interest is only a starting point, like a gateway drug that leads you to something more potent. The monkey sees what matters to it, but the thinking monkey sees, in this, what matters as such. And so what is more difficult to overcome: even when I reconcile myself to the absolute goodness of my situation, I can’t do the same for the sake of others who have it worse. Who could rest easy in such a world? Somehow my philosopher’s contentment then feels like an injustice in itself: that I could be content while they could not.

Like a monkey in a cage getting cucumber, I have taken a perfectly good situation, one with which I was completely content, and made it bad, only by my opinions about justice.

I have made a bad from a good, for the sake of goodness. That’s why it’s a paradox: it goes against itself.

I can’t let myself be happy. And there’s the flaw; there’s the error. Because we can’t iron out all of the injustice in the world by our resistance. There will always be an unequal remainder. What do we do with that? Accept it, surely, and move on. Don’t let it trouble you. Take your cucumber and be glad.

Part Two: A Man in a Locked Room

When introducing philosophy students to different concepts of freedom, a common starting point is to discuss a man in a locked room who chooses to remain where he is.

Is he free?

In a sense, yes, he is free because he does exactly what he chooses to do, and no one can ask for anything more than that. But in another sense absolutely he is not free because we know he could not do otherwise. We say he ‘has no choice’ but to remain where he is because, were he to choose differently, it would make no difference: he cannot leave, and that’s what matters.

Opinions always differ, but most people would say that the man in a locked room is not free, whatever he might feel about it, which tells us something important about freedom: it matters that our choices can make a difference. Choices that don’t or won’t or can’t make a difference aren’t real choices; choices that only make a difference if someone else allows it are restricted choices. There is a reason we consider a prison cell to be a punishment, after all.

It is a distinctively philosophers’ opinion to say that the man in the locked room is free because he is as free as he needs to be, which tells us something else about freedom but probably something more important about philosophers. Epictetus will say: ‘You can chain my leg but not even Zeus can chain my will.’

I relate this back to our monkeys in cages getting cucumbers. When all are where they choose to be, no one complains: this would be the case even if no one could leave. But when one person leaves of their own free will, and then the others try the doors of their cages and find them to be locked: now we have a problem.

Freedom is of the greatest value to us: you might only see that when you are deprived of it, or threatened with its deprivation. And some have more of it than others, without merit. This provokes the caged-monkey’s reaction. Now it doesn’t matter what we are fed: even with a grape, we are still in a cage, and this is intolerable.

And so we see how philosophers are troublemakers. They break chains and shatter illusions, and in that show that there are chains and illusions that bind the ‘ordinary ignorant human being’. When society sees a philosopher freed from its grasp, cages start to rattle. People start to test their own chains and find them binding. It chafes. The philosopher has done nothing – only walked out of the door – but that is enough.

Whether they mean to or not – and often they do not – philosophers cause more problems than they solve.

We are happier if we sit contentedly in the locked room and don’t try the door. As soon as you try, and find it locked, your happiness will be shattered. You will see where you are: a monkey in a cage getting cucumber.

Thought would destroy their paradise.

[…] where ignorance is bliss,

‘Tis folly to be wise.

Thomas Gray, ‘Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College’

Part Three: A Caged Philosopher

Wisdom is a part of our idea of goodness: many would say that wisdom is necessary as a means to achieve goodness, though that is not unequivocal.

While wisdom might sensibly draw limits to knowledge, no one who is trying to do their best would sincerely choose to be foolish. As Socrates might have said: ‘Everything that the human spirit undertakes or suffers will lead to happiness when it is guided by wisdom, but the opposite, when guided by folly.’

So how can it be that being ignorant of your chains is preferable to being aware of it? And yet that is what our happiness suggests, since we are made miserable by learning what we are.

Once again, something bad comes from something good: from wisdom and a recognition of the value of freedom, we are made miserable by becoming aware that we are not free. Like the man in the locked room, we are only ‘free’ when we choose not to try the door, which is no real freedom at all.

I know Socrates’ answer. ‘It is better to suffer wrong than to do it.’ ‘A good person cannot be harmed.’ Etc. Driven by the pursuit of wisdom, and so having thoroughly investigated the matter, he has become convinced of the priority of the good: nothing is more important than living a decent life. Because of this priority, there is a direction of dependence between goodness and happiness that only goes one way: happiness depends on goodness because goodness holds happiness to account, but goodness does not depend on happiness. It follows from this that if you are good, you are as free as you need to be, however you might feel about it.

Who could, whatever your situation, force you to abandon your pursuit of wisdom and goodness? Not even Zeus.

If you are good, you can be happy; and if you are not good, then you are not happy, even though you might go through life smiling. An addict on a high might say that they are happy and trouble free, but we know that this passing contentment is a symptom of a sickness and nothing more.

It is hard to accept. But Socrates (and Plato) would say that you only need to fix your attention on the idea of goodness and everything else will follow. With a thorough investigation of ethics, you will recognise that your ethical life is your responsibility, and yours alone, and consequently what other people do or get is really none of your business.

The monkey who gets the grape is happy: they don’t trouble themselves with their neighbour’s poor reward. But this is a monkey. A thinking monkey recognises, quite simply, what it is to be on the other side of that equation. And so whether cucumber or grape, caged or free, a thinking monkey sees this for what it is, and is troubled.

That is as it should be. A healthy soul is troubled by injustice. Remorse is reassuring: it shows you that you are in your right mind. It is inevitable, then, that whichever side of the equation they find themselves, a thinking monkey will never be free from trouble. The point is not to be troubled by this.

I also know the Stoics’ answer. A drowning man drowns just the same whether he is nearer the surface or not. A little bit of wisdom and goodness might lift you out of the depths, but until you break the surface and breathe the free air you will suffer the same fate as those who have no understanding at all. The point is only to push on until you are indifferent to things that don’t really matter.

I don’t find these answers to be particularly comforting: though if you pushed me I would have to say I agree with their rational accounts, and so I recognise it as a kind of falling short on my part if I don’t accept their conclusions.

I persevere. But I am hesitant. I think there might be a simpler way.

Part Four: A Monkey’s Freedom

When you are a monkey swinging free in the jungle, what do you care if some monkey in a cage gets a grape?

Would you let it trouble you? Would the thought occur to you enough for it to trouble you? If you are content, and are confident that you have the right and the good and would not trade what is yours for what is theirs, you would not so much as think about what others might be doing and getting. And without that thought, there is nothing to trigger your sense of injustice.

The superior person (junzi) makes his eyes not want to see what is not right, makes his ears not want to hear what is not right, makes his mouth not want to speak what is not right, and makes his heart not want to deliberate over what is not right.

Xunzi

Part Five: A Philosopher’s Freedom

This is the goal of a philosopher’s questions about justice and freedom. Not to make-good the injustice, because that is beyond our power, nor to free ourselves from the things that trouble us, because that too is impossible. The goal is to free ourselves from the trouble that these things cause us, not by denying our natural sense of justice, but by realising it in ourselves. We live rightly, and justly, and freely, aligned with whatever truth there is, recognising that this is our duty. If you can achieve that then you will find that you have no complaints.

I know the ultimate condition to be aimed at for a philosopher and it is not a state of perpetual discontent. But there is a distance, for me, from here to there: from where I am to where I could be. The question I have is whether it is right or perhaps necessary to be angry about it along the way. If you recognise that you are a monkey in a cage getting cucumber, ought you allow yourself to get angry at the injustice of your situation, and rattle your cage, for the sake of compelling yourself to break free, even if you know it to be, ultimately, an irrational anger?

Having broken free, you then look back and wonder what all the fuss was about, because it no longer concerns you. You are embarrassed by your childish outbursts. What remains is a charitable compassion, somewhat haughty, meaning perhaps, like Socrates or Zarathustra, you would ‘descend’ back to the depths, becoming a monkey once again, doing tasks, showing your lived example, hoping to lead others to their freedom.

No descent for me yet. I’m not haughty. I’m too busy drowning and grasping for the surface.

Part Six: Does the wise monkey cage itself?

It’s difficult to resolve this paradox because the puzzle that it raises points to nothing less than the final purpose of philosophy, and that isn’t settled.

If the final purpose of philosophy – that is, what we are really pursuing in the pursuit of wisdom – is goodness and truth, then justice cries out to be answered and cannot be ignored: we should not close our eyes to it, no matter the personal cost. And that applies just as much to our thoughtful reflections on injustice, which are necessary to have any clear sight on the matter: we ought to trouble ourselves with these troubling things.

But if it’s contentment that we’re after then, in answering the call of justice, you are a fool, because you trouble yourself with things that you could easily avoid. And that, too, applies just as much to our thoughtful reflections on injustice: we ought not trouble ourselves with these troubling things.

Must it be one or the other? I’m not sure. Aristotle would say that what is best is always found at a happy middle between two extremes of excess and deficiency. While the pursuit of wisdom, and the thoughtful reflection that it involves, might be good and necessary for goodness, you can have too much of even this good thing. Hume would agree.

It seems, then, that nature has pointed out a mixed kind of life as most suitable to the human race, and secretly admonished them to allow none of these biases to draw too much, so as to incapacitate them for other occupations and entertainments. […] Abstruse thought and profound researches I prohibit, and will severely punish, by the pensive melancholy which they introduce, by the endless uncertainty in which they involve you, and by the cold reception which your pretended discoveries shall meet with, when communicated. Be a philosopher; but, amidst all your philosophy, be still a man.

David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

But they are both empirically-minded and because of that limited. Of course if you only look and take your lead from common sense then you will see that the happiest in this world are those that don’t trouble themselves too much with injustice: the happiest seem to be those who don’t trouble themselves with it at all. They enjoy their grapes.

Why does it strike me that there is something wrong with this? Why do I identify with the monkey who gets the cucumber, even though I might get grapes? Why do I side with the angry, those that rattle cages, those that spit in the face of those who stand above them? They clearly aren’t happy, and that isn’t good. But still I think they are right to be as they are. I would rather be like them. I suppose that means I would rather be right than happy.

It’s the old contrast between the right and the good. Happiness is good, but it isn’t always right; justice is right, but it isn’t always happy. If you have to choose between one or the other, you should choose wisely.

Although they might make happiness their aim, even the common-sense-driven empirically-minded philosopher wouldn’t want to rid us of our sense of justice for the sake of the unhappiness it causes us. Aristotle’s ‘happy middle’ applies to ‘negative’ emotions too: there is a right amount of anger, or sadness. The point is not to avoid these bad feelings but only to stop them becoming excessive: not too much, not too little. Anyone genuinely indifferent to the suffering of others would be a strange person and not someone we’d choose to be.

And Hume would say that compassion is the foundation for our ethical sentiments: it is that we see the caged monkey angry and sad that makes us angry and sad, as a result of our natural capacity to ‘feel with’ others, and that only shows that we are functioning normally. We have a word for those who lack this capacity for sympathy: it isn’t ‘philosopher’.

However we look at it, it seems that we ought to be troubled by injustice, and that means the thinking monkey is doomed to a kind of moral tragedy. We cannot be happy while there is injustice, and there is always injustice. Therefore, we can never be happy.

What a shame. We must find a way to live with it. We must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Start again at the beginning. ‘Nothing too much.’ The wise person moderates their appetites and draws limits to their desires. Are there wisely-imposed limits to our appetite for justice, happiness, and freedom?

Surely yes, because they limit each other. For the sake of happiness, I limit my sense of justice; for the sake of justice, I limit my happiness. For the sake of them both, I limit my freedom: it’s out of duty that I do this and in the end I am happier for it.

But even a self-imposed limitation has its wisely-imposed limits – even temperance must be tempered – and so for the sake of what is right and good I break free. I take a philosopher’s freedom, finding happiness in rightness, and enchant myself by writing bits and pieces that I then throw away. I never liked cucumber anyway.