-

The Rion: An Ancient Dialogue for Our Times

The Exile: Very nice to meet you, Rion. Am I talking to you at home? Rion: No, I’m in a hotel just outside of Bullton right now; I’ve been here to give a talk at a conference on mental health. Ex: And did they have many philosophers talking at the conference? Ri: Oh for sure, […]

-

Why Do I Write?

Why do I write? When I say write I mean writing philosophy. I could try writing other things, I suppose, but what I have been writing up to now is philosophy. And not only writing it but also putting it online for all to see. What is the purpose of this? […]

-

Diogenes the Cynic

Diogenes sees a mouse, happily running about, not looking for money or prestige, and finds a lesson in the mouse’s behaviour: Nature has given us a relatively easy life, but we’ve overlaid it with nonsense. We make life difficult for ourselves by wanting more than our nature needs. Diogenes implores us to realise this, offering us a walking talking living breathing lesson with his own example. […]

-

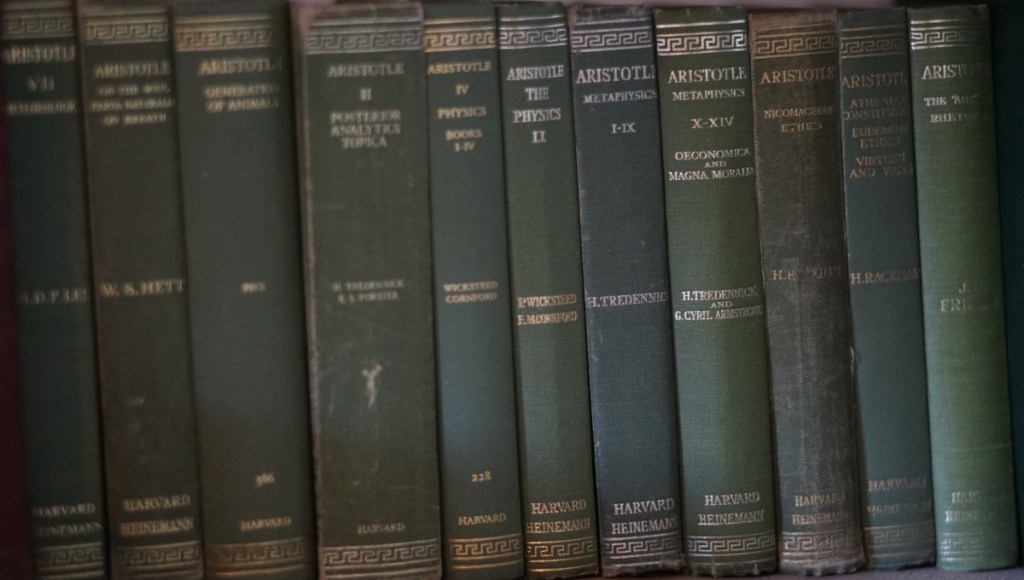

Two Philosophical Approaches

Two approaches have been pre-eminently influential in philosophy. One approach says that we should trust what we think over what we see, because our perception is unreliable: we should place ‘mind over matter’. The other approach says that we should trust what we see over what we think, because our thinking is unreliable: we should place ‘matter over mind’. Both approaches have consequences, good and bad. […]

-

Plato’s Political Philosophy

It might sound odd to say that Plato’s discussion of political philosophy shows us important truths about how to live well. For many of us, thinking about politics is likely to make us feel more anxious and depressed, not less. But it makes more sense when you consider why Plato is discussing political philosophy in the first place. […]

-

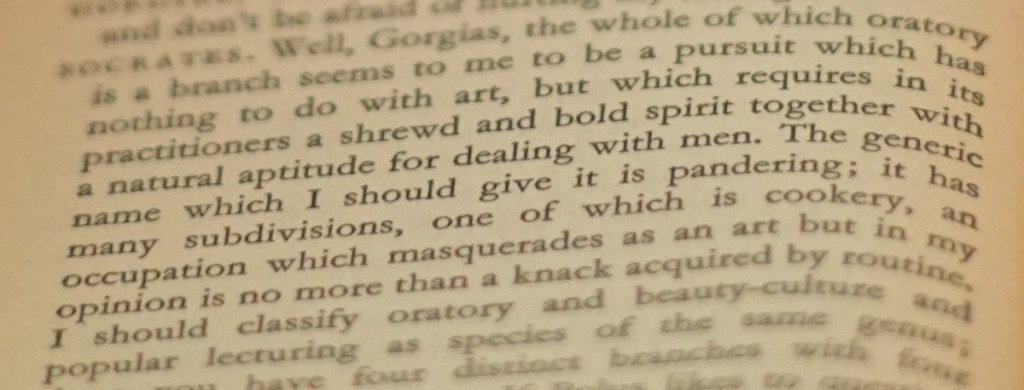

Pandering

Recently, I’ve been running a series of posts about the problem of evil. Much of it is recycled from my book on the subject. The main motivation for this is SEO: I want to teach the Google bots that my writing here is what should be read, rather than my old academic writing. Ancient Greek philosophers had a word for this kind of thing: κολακεία. It is variously translated as ‘pandering’ or ‘flattery’. It means playing to the crowd. In my case, it means trying to give the Google bots what they can understand. […]

-

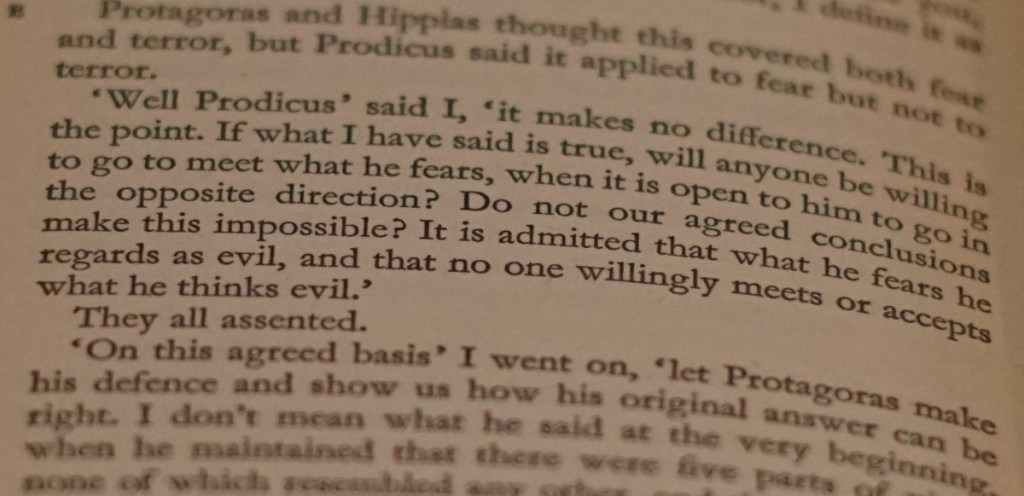

The Protagoras: How To See What Isn’t Said

Read superficially, the Protagoras doesn’t appear to tell us much of any use that isn’t told better elsewhere – unlike the Meno, which has some more memorable features – so if you’re teaching (or learning) an introductory course on Plato, you might be inclined to skip this one altogether. That would be a shame, because it’s another excellent example of Plato’s ‘writing with layered intentions’; and if you can uncover the meaning in the Protagoras, you will be well-equipped to discover more meaning in the other Platonic dialogues. […]

An experiment with philosophy as a way of life