-

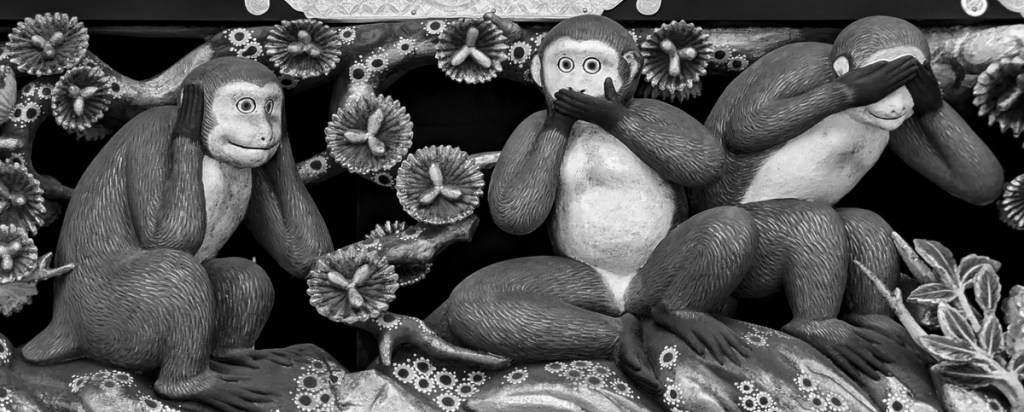

Too Good to be Happy: A Paradox for the Good

Justice is a part of our idea of goodness, unequivocally. But having a sense of justice makes you sensitive to injustice. With this sensitivity, any injustice is liable to make such a person miserable. And there doesn’t seem to be anything good about being miserable. That seems to me to be a paradox of goodness, whereby something unequivocally bad comes from something unequivocally good. Justice is good, and happiness is good, but having a sense of justice makes us less happy. Having one good seems to deprive us of another. I wonder what the solution to this puzzle might be.

-

Diogenes the Cynic

Diogenes sees a mouse, happily running about, not looking for money or prestige, and finds a lesson in the mouse’s behaviour: Nature has given us a relatively easy life, but we’ve overlaid it with nonsense. We make life difficult for ourselves by wanting more than our nature needs. Diogenes implores us to realise this, offering us a walking talking living breathing lesson with his own example. […]

-

Natural Self-Interest

Over the ages, many philosophers have looked to ground ethics in our natural and apparently innate tendency towards self-preservation. It is often termed ‘self-love’: we have a deep need to look after our own interests. An infant cries when its needs are not met; an adult wants what pleases it. This would seem to be a truth so universal that we would call it a natural law, like gravity. […]

-

Two Philosophical Approaches

Two approaches have been pre-eminently influential in philosophy. One approach says that we should trust what we think over what we see, because our perception is unreliable: we should place ‘mind over matter’. The other approach says that we should trust what we see over what we think, because our thinking is unreliable: we should place ‘matter over mind’. Both approaches have consequences, good and bad. […]

-

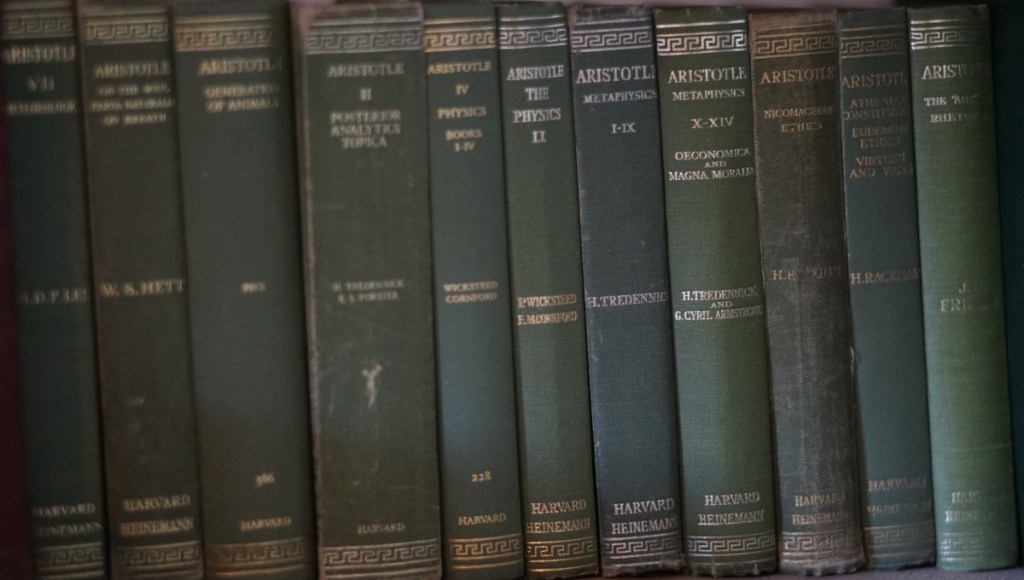

Aristotle’s Practical Wisdom

According to Aristotle’s view, wisdom lies in the ability to identify and choose the happy middle, for you, relative to yourself and your purposes. One part of this is philosophical: you need to look, think, and understand what the happy middle is, for you, for any given virtue. The other part is practical: you need to choose what you identify as the happy middle. This choice is an action; it is something that it done, not only something that is thought about. […]

-

Aristotle’s Happy Middle

Look around you, and have a think, and draw up a list of qualities that some people have that you admire or appreciate. What comes to mind? It’s not for Aristotle (or me) to list the virtues, nor identify their purposes, because you can do this for yourself based on your own observations and reflections. What Aristotle points out is that virtues are very important, but you can have too much of a good thing. […]

-

The Purpose of Life, According to Aristotle

What is a good life? What is ‘Good’? Socrates and Plato would say that these are very difficult questions to answer, requiring an almost other-worldly kind of wisdom. Not so for Aristotle, whose method brings us right down-to-earth. What is ‘Good’? Well, look around, what do you point at and say ‘that is good’? […]

-

The Protagoras: How To See What Isn’t Said

Read superficially, the Protagoras doesn’t appear to tell us much of any use that isn’t told better elsewhere – unlike the Meno, which has some more memorable features – so if you’re teaching (or learning) an introductory course on Plato, you might be inclined to skip this one altogether. That would be a shame, because it’s another excellent example of Plato’s ‘writing with layered intentions’; and if you can uncover the meaning in the Protagoras, you will be well-equipped to discover more meaning in the other Platonic dialogues. […]

-

The Meno: How to See What Isn’t Said

The Meno is one of the most complicated yet clear examples of Plato’s way of ‘showing one thing whilst saying something else’. Elsewhere I’ve described this as writing with layered intentions: on the surface there are some philosophical arguments with which you may or may not agree; beneath that there is a show of doing philosophy in a certain way; and beneath that there is a provocation to do it yourself. What’s on the surface isn’t really what the dialogue is about. […]

An experiment with philosophy as a way of life